Workplace 工作场所

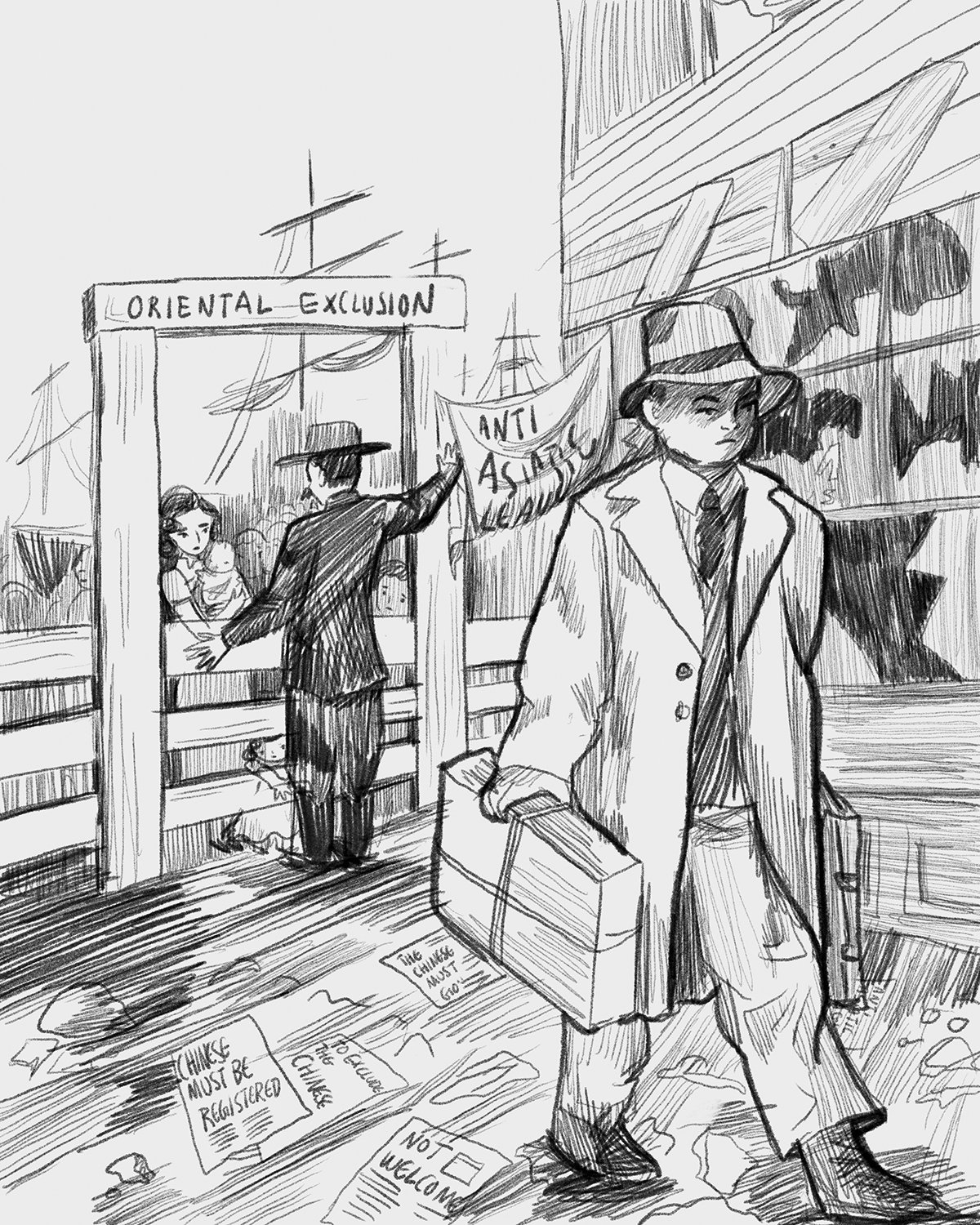

Following the cessation of construction on the railroad, many Chinese immigrants found themselves without work in an environment with increasingly racist feelings towards them. Most white businesses would not hire Chinese men, forcing them to create their own businesses.

One of the most common businesses started by Chinese men in the early 20th century was a hand-wash laundry. Laundry work was seen as undesirable and typically reserved for women. Laundries did not require a significant financial investment from their owners to start them up. In 1893, Vancouver legislated that laundries could not be opened outside of its Chinatown.

Laundrymen experienced a great deal of hardships. Racism was commonplace, white customers did not understand the characters printed on laundry tags, using it as an avenue to bully and harass. Media portrayals for many years have made heavily accented laundrymen the punchline of hurtful jokes. The 1907 Race Riots in Vancouver and other major cities saw Chinese-owned businesses attacked. This kind of destruction of property was not limited to the riots, however, with Chinese laundries being frequently targeted for robbery and other crimes.

Casual Chinese eateries could be found in the 1860s in Barkerville, BC. More established ones could be found in the 1890s in Vancouver’s Chinatown, and even earlier in Victoria’s Chinatown. The fare was often a mix of Western and Chinese foods. Chinese chefs were forced to adjust their recipes, with most dishes originating from Cantonese cuisine. These new meals combined Western tastes, and available ingredients, with Chinese cooking techniques.

-

在加拿大太平洋铁路修建完成之后,许多中国移民发现自己被迫失业。当时周围的环境对他们的种族主义情绪日益严重,大多数白人企业不愿雇用华人,这迫使许多华人自己创业。

在20 世纪初,华人创办的最常见的企业之一是手洗洗衣店。洗衣工作被视为不受欢迎的工作,通常只有妇女才能从事。但开洗衣店并不需要店主投入大量资金。1893 年,温哥华立法规定洗衣店不能开在唐人街以外的地方。

华人洗衣工饱受艰难困苦,种族歧视早已是司空见惯。例如白人顾客以不懂洗衣店标签上的文字为由,大肆欺凌和骚扰华人洗衣店。多年来,媒体对洗衣工的描述带有浓重口音的洗衣工成了广为流传的歧视笑柄。1907 年在在温哥华和其他大城市发生的排亚种族骚乱中,华人企业商铺屡遭袭击。然而这种破坏财产的行为并不仅限于暴乱,华人洗衣店也经常成为抢劫和其他犯罪的目标。

餐馆则是华人开设的另一个常见行业。加拿大第一家中餐馆于 1901 年开业。那时中餐馆的供应的菜肴通常都是中西合璧。除此之外,许多华人厨师选择对现有的粤菜食谱进行改良。这些菜肴将西方口味,现有食材,以及中式烹饪技术进行了完美结合。

Chinese Opera 粤剧

Opera theatres were one of the most important cultural aspects of the Chinese diaspora living in British Columbia. Several theatres operated both in Victoria and Vancouver. These places operated as the faces of the Chinese community, extending Chinese culture to Western people. They were visited by the thousands of Chinese people living in the Lower Mainland, seeking to experience their own culture in a place far away from home.

Chinese theatres have been in Victoria for as long as Chinese immigrants have, with the first cropping up around 1860.

The theatres had to contend with the head tax laws of the 1885 Immigration Act. Some theatres avoided head tax restrictions, by paying a $500 bond for actors. The bond lasted for six months but could be extended for up to three years.

Sabbath laws also hampered performances. Fines were issued to theatres for performing on the Sabbath, though theses laws were able to be circumvented. Chinese managers were able to convince the governing bodies that the shows were religious, a truthful statement for some plays, allowing performances to go ahead.

Despite these restrictions, theatres expanded, and new ones were built to accompany a growing Chinese community in Vancouver and Victoria. The theatres diversified their performances, offering vaudeville performances with white actors to draw in Western audiences.

Although anti-Chinese sentiment continued to grow during the early 20th century, the opera continued to have success with the community. One of the first stars of Vancouver’s Chinese opera scene was Zhang Shuqin, paid over six times the average salary of a performer. Crowds went so far as to pitch apples at performers thought to have wronged Zhang.

-

粤剧剧院是居住在不列颠哥伦比亚省的华人华侨最重要的文化活动之一,尤其是在维多利亚和温哥华。这些地方作为加国最大的华人社区的所在地,向其他族裔传播中国文化。成千上万居住在低陆平原的华人有幸到这些剧场观看粤剧演出,在异国他乡体验自己的文化。

维多利亚的华人剧院的历史与当地的华人移民的历史一样悠久,最早的剧院可以追溯到1860 年左右。

这些华人剧院必须遵守《1885华人移民法》中的“人头税”法。一些剧院通过为演员支付 500 加元的保证金来规避人头税限制。保证金期限为六个月,但可延长至三年。

除此之外,加拿大的安息日法(Sabbath Laws)也妨碍了剧院的运营。政府会对在安息日(周日)演出的剧院处以罚款,但在某些情况下该法律是可以规避的。因为华人剧院的管理者能够让管理机构相信演出是具有宗教性质的、因为对于某些剧目来说的确如此,只有这样演出才得以继续。

尽管有种种限制,加拿大的粤剧院不断扩大,新的剧院也随之建成,以满足温哥华与维多利亚日益增长的华人社区的需要。剧院的演出形式开始多元化,并聘用白人演员以及增添耍表演,以吸引不同族裔的观众。

尽管 20 世纪初的反华情绪持续高涨,但粤剧在温哥华和维多利亚仍然取得了成功。温哥华粤剧戏曲的首批明星之一便是张淑琴(音译),她的工资是普通演员的六倍多。当时的观众甚至向被认为得罪张淑琴的演员扔烂菜叶。

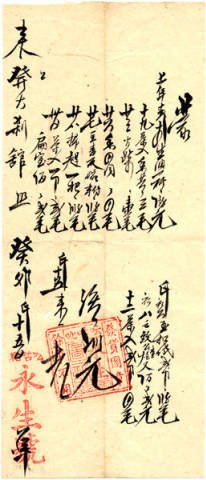

Incomes statement of Wing Sang Company, 1903, UBC Library Digital Collections, Public Domain.

Archival photo of Yip Sang, 1845-1927, one of the patriarchs of Vancouver’s Chinatown. Handout The Vancouver Sun https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/canada-150/canada-150-yip-sang-the-unofficial-mayor-of-chinatown

Sending Money Back Home 寄钱回家

For most of the history of Chinese immigration, remittances, or money sent to relatives in China was handled by fi rms, alternatively, a trusted friend or neighbour returning to China could deliver money. There was a strong sense of trust and community accountability.

During World War 2 Canada began to require permits for money sent abroad, setting a maximum rate of $25 per month. The government also restricted who could handle money transfers, taking the authority out of the hands of local Chinese fi rms. This caused many, such as the Wing Sang Company, to deteriorate greatly as the practice of transferring money changed with the new regulations.

One could send more than $25, however, it required extensive permits to be filled out. The authority was placed in the hands of China’s Nationalist government, giving them agency over their diaspora, this allowed the Chinese government to further tax the diaspora. They were able to set the rates of exchange unfavorably, to profit themselves.

In theory, Chinese workers should have qualified for tax deductions since they had dependents, albeit in China. It took until 1942 for the deductions to come into effect.

By 1943, Canada began to pursue perceived tax fraud and rejecting tax deductions, with the government claiming their need to support dependents was unverifiable. Many Chinese Canadians lacked the necessary documentation, or legal support to pursue their claims. Racism made this even more difficult, as many held a bias that Chinese workers did not have dependents, and were lying to see reduced taxes, although a majority were married with families in China.

-

中国移民在大部分时间里,都是通过汇款公司给在中国的家人寄钱的。有时华人也会请返回中国的可信赖的故交帮忙转交钱款。当时的华人社区有一种强烈的信任感和社区责任感。然而,在加拿大政府残酷的战时政策极大地改变了汇款方式之后,这种信任消失了。

战争期间,加拿大开始要求向国外汇款必须申请政府许可,并规定每月最高汇款额为 25 加元。同时加拿大政府还限制了谁可以代理国际汇款,将权力从当地华人公司手中收回。这导致许多公司,例如永生公司,的经营状况大大恶化。

后来,个人汇款金额被允许超过 25 加元,但需要填写大量许可证与通过繁的手续。这同时也使中国国民党政府拥有了对海外华人对华汇款的代理权。这使得中国政府可以进一步向侨民征税,并制定不平等的汇率牟利。

从理论上来讲,历史上的华工应该有资格在加拿大享受减税资格,因为他们在中国有需要赡养的家属。但直到 1942 年,这项减税政策才在华人群体中开始生效。

然而到了 1943 年,加拿大以追查税务欺诈行为为由,拒绝为华人减税。联邦政府声称华人无法证实其有需要赡养人,因为许多华裔加拿大人缺乏必要的法律文件。种族主义使这一问题变得更加棘手,当时的政府对华人充满了偏见:他们毫无根据的认为华人没有受抚养人,他们撒谎是为了获得减税。事实上大多数华人已婚并在中国有家庭。

World War II - The Home Front 二战 – 后方战线

Over 600 Chinese Canadians fought in the Second World War, many more would aid the war effort on the home front despite facing racism across Canada.

The Canadian government of the time pushed racist policies affecting many racial minorities. Ministers frequently did not look to nationality, but to race, when looking for potential enemies.

There was a reluctance among policymakers to allow Chinese Canadians to train for the home defense units or to join the military. They felt that if they were to give Chinese Canadians this opportunity, they would be able to lobby for enfranchisement after the war.

In the early war years Chinese Canadians were barred from serving in any branch of the military. Very few were able to bypass this restriction.

The community itself remained divided on whether they should volunteer to fight. Some felt that they should not serve a racist country, others however saw this as an opportunity to achieve recognition. By fighting, they hoped to claim citizenship. Chinese Canadians were in theory offered the same rights as anyone else. This however was not true in practice, it took many more years for race-based immigration policies to be dismantled, and even today, racism and discrimination are still felt in Canada’s Chinese community.

-

有 600 多名加拿大华人参加了第二次世界大战,另有更多的华人在后方协助战争。尽管当时他们在加拿大面临着各种各样的种族歧视。

当时的加拿大政府推行种族主义政策,这一举措极大地伤害了许多少数族裔。官员们不看国籍,只看种族,认为任何非英裔加拿大白人的人都是潜在的人。

根据种族主义观念,少数族裔被任意划分到不同的行业。例如,意大利裔加拿大人被安排从事重工业工作,官员们声称他们更适合这些工作。中国人、日本人、和原住民则被迫从事农业工作。

政府官员不愿意让华裔加拿大人接受部队的训练,更不愿意让华裔加拿大人参军。他们认为,如果给华裔加拿大人机会参军,华裔加拿大人就能在战后游说他们获得公民权。

战争初期,加拿大华人被禁止在任何军种服役,能够绕过这一禁令的人寥寥无几。

与此同时,在是否应当入伍参战的问题上,加拿大华人社区本身也存在分歧。一些人认为,他们不应该为一个种族主义国家服务。其他人则认为这是一个追求平等的机会。他们希望通过参战获得公民身份。二战后,加拿大华人在理论上享有与其他族裔同等的权利。但实际上并非如此,基于种族差异的殖民政策直到几十年后方才取消。即使到了今天,加拿大华人社区仍然能感受到种族主义和歧视。

Force 136 men await in England for repatriation to Canada. Courtesy of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum.

Associations 会馆

Around 80% of the Chinese men living in Canada during the first half of the 20th century were married, with families at home in China. This lack of family support brought about an adaptation of traditional associations.

These organizations provided support and sought to help many of the people, many who came from rural lifestyles in China. They provided social services and housing support, particularly for older members of the community. These associations were often involved with banking services. Perhaps most importantly though, they provided friendship and camaraderie.

There were many types of associations in Canada, but their number continued to grow as immigration restrictions got tighter, they reached their peak during the years of the exclusion act. Six groups drew membership based on the town or city, this started in 1898, by 1937, there were 17. An even more dramatic rise is visible in associations based on shared surnames; there were 26 groups in 1923. A few years later, in 1937, there were 46 groups.

One of the most prominent was the Chinese Benevolent Association of Vancouver, founded in 1896. This group has been said to be the de facto government of Vancouver’s Chinatown. It was founded in part by Yip Sang. Yip Sang was a wealthy businessman and prominent community leader. He was able to use business and political connections in Canada and China to support the residents of Chinatown. One of his most important ventures was a remittance service.

-

20 世纪上半叶生活在加拿大的华人男性中,约有 80% 已婚并组成家庭。然而由于种种限制,华人男性难以将家人带来加拿大。在这种缺乏家庭支持的情况下,推动了华人会馆的兴起。

这些会馆为许多新来的华人移民以及社区中的中老年人提供支持和帮助,包括提供社会服务和住房。除此之外,这些组织同时也提供汇款服务。但最重要的是,它们提供友谊和陪伴。

加拿大有多种类型的华人会馆。随着移民限制的收紧,会馆的数量持续增长。在《排外法案》颁布后,这些组织的发展达到了顶峰。1898 年,加拿大共有六个同乡会馆。而到了 1937 年,这一数字达到了 17 个。另外以共同姓氏为基础的宗亲会在1923 年共有 26 个团体。几年后的 1937 年,这样的组织多达 46 个。

其中最著名的是成立于 1896 年的温哥华中华会馆(Chinese Benevolent Association of Vancouver)。有一种说法称该团体是温哥华唐人街事实上的政府,其创始人之一便是叶生。叶生是一位富有的商人和杰出的社区领袖。他常常利用在加拿大和中国的商业往来与政治关系来帮助唐人街的居民。叶生最重要的生意之一是汇款服务。

Bachelor Society 单身汉社会

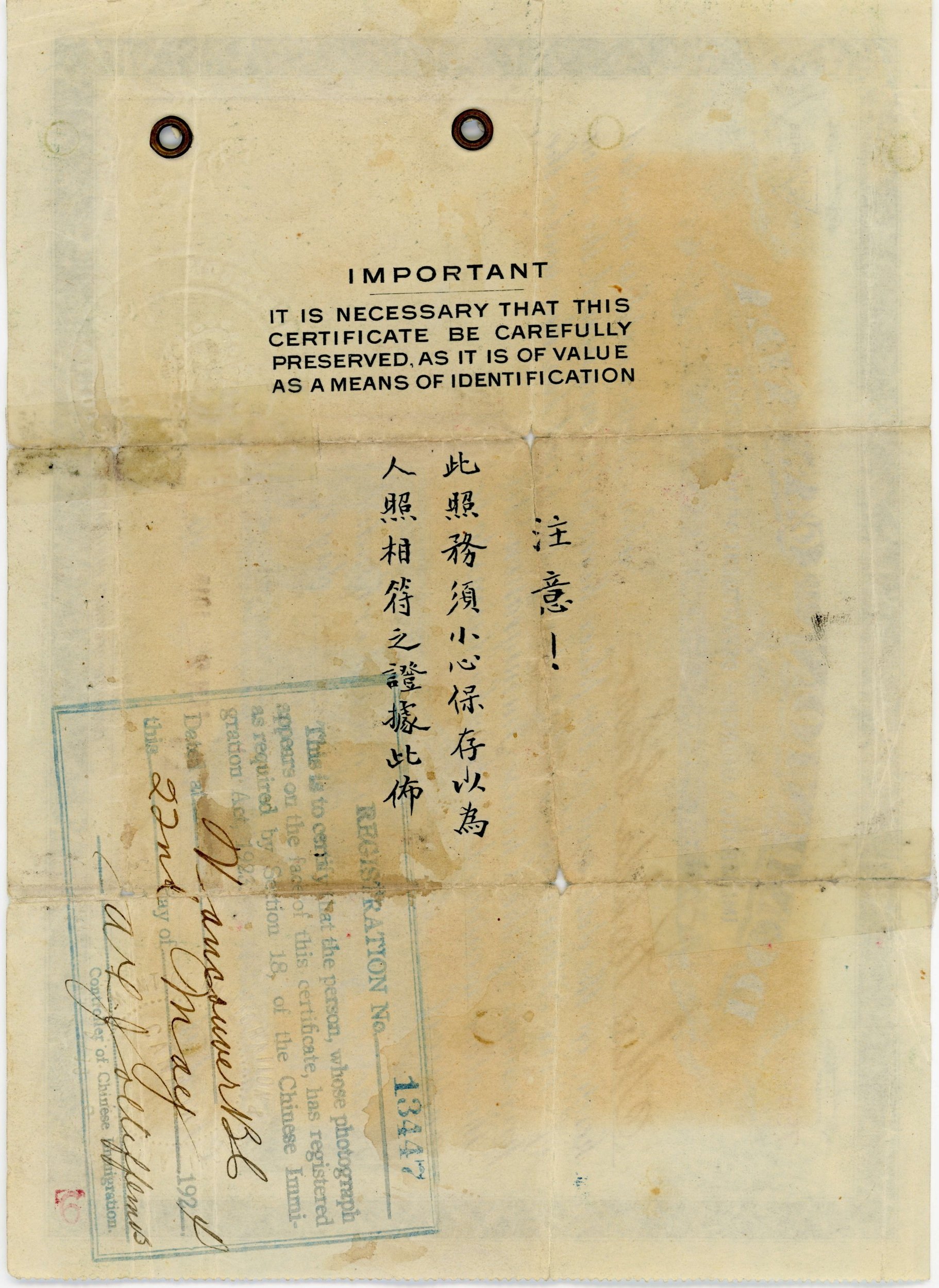

The 43 Harsh Regulations was the name Chinese Canadians gave to the 1923 Immigration Act. Today, it is more commonly referred to as the exclusion act. While previous legislation heavily restricted family members through head taxes, some were able to come. This changed with the 1923 act. The clauses of the act forbade Chinese Immigration to Canada, except under very specific circumstances.

The lack of women and families was significant. There was a 28 to 1 ratio of Chinese men to women during the years of the immigration act. This created the so-called “Bachelor Society.” These men sent money back to China to support their families, yet were unable to reunite with said family. Yeung Sing Yew, who immigrated in 1923, did not meet his daughter until 1965. Yeung Sing Yew’s grandson, Dr. Henry Yu, recalls how his grandfather, was excited to finally be able to show off his family.

The lack of familial support was felt by many. Groups and clubs worked instead to help their members, with funds organized if people were injured, or needed a place to stay.

The exclusion act allowed individuals to leave Canada for a period, normally less than a few years. Some returnees sold their immigration documents, allowing someone else to enter Canada under their name. These are the Paper Sons, named as many of them entered as the “son” of an existing resident during the head tax era. Paper Son also refers to those who arrived on forged documents. While the true extent of these men can never be known for certain, it is estimated that some 11,000 men came to Canada as Paper Sons at some point.

-

《43 苛刻条例》是当时的加拿大华人对 1923 年《华人移民法》的称呼。如今,它更多地被称为《排华法案》。虽然之前的人头税对家庭成员移民进行了严格限制,但仍有一些华人能够将家人带来加拿大。1923 年的法案改变了这一状况。除了极少特例以外,该法案条款全面禁止中国人移民加拿大。

在如此情形之下,华人社区女性移民数量严重不足。在《排华法案》实施期间,华人男女比例为高达 28:1。这就形成了所谓的”单身汉社会”。这些男性华工把钱寄回中国赡养妻儿老小的同时,却不得不与家人隔重洋。1923 年移民来加的杨星耀直到 1965 年才见到自己的女儿。杨星耀的外孙余全毅博士(Dr. Henry Yu)回忆道:父女团聚之后他的外祖父时常兴奋地向大家炫耀他引以为傲的家人。

许多华人都痛感家庭关怀的缺失。但这却进一步推动了华人会馆的发展。如果有人受伤或需要住处,会馆会提供资金来帮助他们的成员。

《排华法案》允许个人离开加拿大一段时间,通常不超过几年。一些回流者则选择出售了他们的移民文件,允许他人以他们的名义进入加拿大。这些以他人身份移民加的人被称作”纸生仔 (Paper Sons)”,因为他们中的许多人是以”儿子”的身份换取人头税的减免方才进入加拿大。”纸生仔”也指那些持伪造证件抵达的人。虽然这些人的真实人数。虽然这些人的真实人数永无法确定,但据估计,大约有 11,000 人曾以 “纸生仔”的身份来到加拿大。