Breaking Bread

Bread and History

Romans and Bread

Romans for many years did not eat bread in the way that we think of it. For a long time, porridges and flat, unleavened cakes cooked on coals or hot slabs were the most common ways to eat grains in ancient Rome. This changed in the year 168 BCE. Perseus I was defeated by the Roman Legions, many of his men taken as slaves. These Greek prisoners brought with them the knowledge of leavened bread, the loaf that we think of today when bread is mentioned.

-

Bread quickly became the new staple of ancient Rome, spreading across the Empire. It was leavened similar to modern sourdough, with a fermented starter being used. Made from day old dough that had been left out. Yeasted dough was not unheard of either though, word spread from Gallic peoples about dough made with brewers’ yeast that produced an extremely light bread. It was eventually brought to Rome, but the fermented dough was the more common of the two. Perhaps the second most famous Roman city, Pompeii, alone contained over 40 bakeries, with many homes having personal ovens for baking, this demonstrates just how prevalent and important bread was to everyday Roman life

Romans had nuanced and complex tastes for their bread. It was far from simple. There were many different types of bread, owing to the ways that it can be shaped and prepared, as well as the different grades of flour used in its production. The finest and highest quality flour that made white breads was saved for the nobility and upper classes, with coarser whole wheat flour being used to make bread for the poorer among the populous. Bread was frequently decorated or shaped for special occasions. Loaves may be formed into a multitude of shapes from braids to hearts, or even spoked wheels. Bread wasn’t just made with the most basic ingredients, when available, milk, honey, or eggs could be added to enrich the bread, and add new depths of flavour. It was also common for bread to include poppyseeds or other fruits and nuts atop its crust. (Rubel 35) These adornments and enrichments show that bread was more than a staple food for the Roman people, it was an important part of culture, with people putting a great deal of time and effort into making bread not only taste good but look good too.

Bread in ancient Rome was the centerpiece of what can be described as on of the first social welfare systems. Those who had fallen on hard times in the City of Rome would be eligible to receive a token, made of lead, that could be exchanged for flour or grain in order to bake bread. In time the system expanded to encompass farmers, and members of the military, and soon, recipients would receive two loaves made for them each day, instead of the ingredients to do it themselves. This sort of social welfare is indicative of a culture that centers itself so much on bread, that welfare is paid out in standardized pieces of bread.

Since Roman bread was regulated, bronze stamps were created, it bore one’s name, and was placed on a piece of bread as it was baking, when done, an imprint linking the bread to its creator was left in the loaf. This served manifold purposes. Should a baker attempt to defraud his customers by baking loaves that were too small, or did not use the right ingredients, it could easily be traced back to him, allowing the authorities to hold them accountable. These bread stamps were also employed by ordinary people, in many places, bread was prepared at home, and then made in a community oven, the stamps were an easy way of keeping track of who’s bread was who’s, as well as deterring theft, (so long as the thief didn’t eat the section of stamped bread!) The stamp also served as a point of pride, bakers wanted people to know who made their bread, and didn’t want anyone taking credit for expertly made loaves, in this way, the stamps can be seen as a quality assurance seal.

Bakers were seen as extremely important members of the Roman community, after all, they were the ones who kept everyone fed. Roman Bakers often found themselves as civic officials, their trust owed to their trade. When renowned bakers died, people built massive tombs for them, memorializing them forever.

Romans had an important relationship with their bread. It was a staple food that fed an empire. It was regulated, yet people still added flair, interesting designs, shapes, and flavours were added into bread, it went beyond the simple wheat bread loaf. Bread was the centerpiece of one of the first social welfare systems. Being how the less fortunate were supplied by the government, as opposed to monetary payouts.

Fresco in Pompeii depicting customers buying bread. Photo courtesy of Wikicommons.

Horsebread

As drivers of the Tudor-era British economy, there was a widely-held belief that horses deserved nothing but the best when it came to sustenance. In one form or another, protein and carbohydrates needed to be efficiently delivered to resting horses in a compact, travel-sized object that could be stored for several days while on the road – an idea that sounds remarkably like bread. Enter Gervase Markham, a 16th-century sportsman involved in discussions amongst upper-class horse owners thinking about the health and longevity of their animals. Markham took this quest seriously when he, while trying to reform the training and exercise regimen (including diet) of his racehorses, wrote a guide for horse health. In it, he decreed certain types of bread to be a key part of a healthy horse’s diet. In seeking to improve the health of his racehorses, Markham started a trend that, today, is not only a look into a quirky alternative bread, but a fascinating view into English conceptions of class.

-

Part of a larger set of instructions for a horse’s diet, Markham’s recipe for horse bread was extremely nutrient-rich, dense in calories, and hearty, intended for horses to eat to regain strength after a particularly grueling day. As “elite breads for elite animals”, horse breads were not initially available for horses used on farms or in common roles. The typical early horse bread was coarse and unrefined, baked into flat five-pound pucks that could fit into a saddlebag, and usually made from a combination of oats, seasonal legumes, bran, rye, maize, and acorns. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, horse bread became so common and viewed as so essential that some bakeries were making more bread for horses than for humans! As with many other foods, horse bread came under the purview of laws governing its production. More than just there to ensure quality, bread laws also helped guarantee that horse bread would remain widely available and, therefore, the British economy could keep chugging along.

Horse bread eventually came to be for more than just horses. Because it was made from a mix of easy-to-access ingredients, in addition to gatherable foods such as acorns, horse bread helped many peasants get through times of famine, sustaining them through poor crop yields and when they could not afford healthier white bread. But with consumption came stigma. As white bread, which was supposedly purer, was considered the pinnacle of nutrition at the time, the hard, brown discs of horse bread sat firmly at the bottom of the culinary hierarchy. Yet for many lower-class Britons, it was a consistent and sustaining food for lean times.

In the early 19th century, horse bread fell out of favour. As railways opened and largely replaced horses, the idea of horse bread became a relic of the past. Although some contemporary horse owners still follow Markham’s recipe very closely for its purity and connection to the past, oats and pellets have largely replaced horse bread.

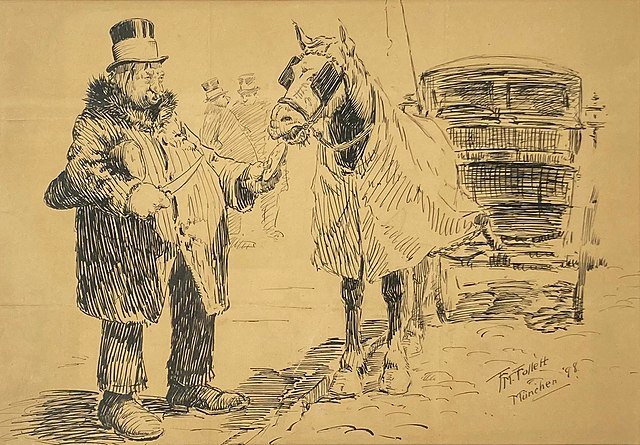

Illustration of man feeding bread to a horse. Photo courtesy of Wikicommons.

Meat vs Bread in the WWI Ration

Napoleon Bonaparte once said that “An army marches on its stomach,” for almost all of history the militaries of the world have had to keep their troops fed, while different cultures and time periods have changed what meals are eaten and what food is allotted to each soldier, everyone had to eat. Bread is a staple food the world over, and prepared right, it can last for many years, it has many names, but is most known as hardtack or ship’s biscuit. Hardtack was a staple of rations in the American Civil War. This biscuit is made with water, salt, and flour, then baked until hard. It makes a clack sound when hit together, not unlike two pieces of rock. Hardtack was not favoured for its taste or texture, but for its nutritional value to keep a person fed, and for its ability to last effectively forever.

Hardtack continued as a ration into the First World War, being labeled in ration orders simply as biscuiT. This ration could be carried in the field by the individual soldier and eaten in moments of downtime. Along with this field ration of biscuit though, is that of preserved meat. This may be pickled beef, corned beef in a can or some other type of salt meat. This is seen as the primary part of the ration. Soldiers remember the meat more than they do their bread ration. It became the centerpiece, although it may not have been all too loved, it is recalled fondly by many veterans as a small piece of comfort in the horrors of war.

Looking at the amount of meat and bread issued daily to soldiers, it is clear that by WW1, meat had become the dominant part of the meal. The amount of meat is always listed first on the ration order. Followed by everything else. In British rations, meat and bread are given in equal quantities. Meat had taken the spotlight from bread as the center of the soldier’s meal. German rations were notably different though. As early as 1916, it can be seen that the German rations are notable smaller than their English counterparts. They receive far more types of bread, specifying different types, ranging from biscuits to loaf bread, though the overall amount is similar, if not slightly smaller. The amount of meat received by the German soldier is notably less, owing to the resource and material shortage that Germany was suffering.

At the time of the First World War, the world was better understanding the role that different parts of food played. People began to understand what made certain foods nutritious and the requirements for healthy living. This was just as, if not more important to the soldiers fighting the war. After all, an army does march on its stomach. Canned fish became an important part of the British army’s ration. Here in British Columbia, as well as Alaska, Washington and Oregon, fish canneries sought to show the value of canned salmon as a military ration in order to expand their industry. This worked, the British army made canned salmon an important part of their ration supply, as meat could be hard to acquire at times. The army was dedicated to ensuring that protein found its way into the ration supply of its troops. This importance of canned fish helps to mark a shift away from bread as the main part of a meal and towards meat and fish as the centerpiece, with bread being supplementary to that.

Gluten in Bread

Celiac disease is a hereditary, autoimmune digestive disorder that produces a sensitivity to gluten. When a person with celiac disease eats gluten, their body attacks the small intestine, causing bloating, diarrhea, constipation, gas, major abdominal pain, and nausea. Celiac disease prevents the absorption of food’s nutrients, and can lead to starvation if left untreated.

-

The first account of celiac disease was in 100 AD when greek physician Aretaeus of Cappadocia described a patient who could not digest food.it was named coeliac diathesis, from the greek word koalia meaning abdomen. For centuries there was no cure or treatment; many diets were tried, the most famous being the Banana diet.

During the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944 Dutch physician Dr. Willem Dicke changed the understanding of celiac disease, when he made the correlation between wheat and celiac patients.

When German troops blocked off food supplies, Dr. Dicke noticed that children with the disease were improving and gaining weight. When the Allies delivered bread after the famine, his patients relapesed into chronic pain. For Dr. Dicke the correlation between bread and celiac disease was obvious and he developed a wheat-free diet for his patients.

In the 1980’s, Dr. Anca Safta discovered that people can have a sensitivity to gluten without being celiac.the recent increased spread of Western diets across the world has resulted in more celiac patients.

Photo courtesy of Wikicommons.

Bread in Coquitlam’s Past

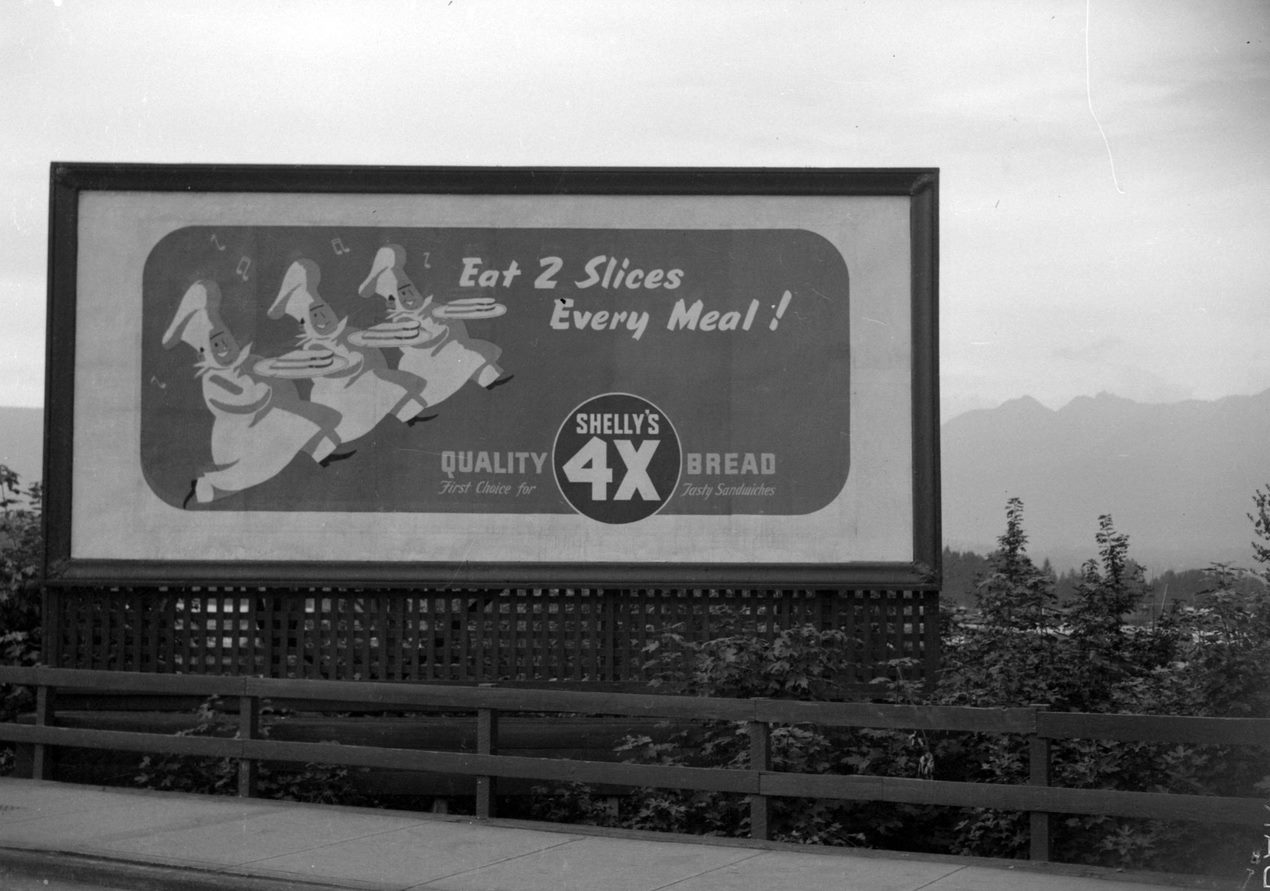

Shelley’s 4x Bakery Billboard. Photo courtesy of Vancouver Archives A12215.

The first bakery in Maillardville, was established by James Russell at 1125 Cartier Avenue in the early 1920’s. in 1927, he purchased a lot near the corner of Marmont and Brunette Ave and built a large bakery with state of the art equipment. Bread was delivered from the bakery to families in Maillardville. George Sharrock was the delivery man for many years until around 1936. During the Depression he would leave bread regardless of whether people could pay for it. the bakery closed in 1948.

Shelly’s 4X bakery was another bread delivery service, delivering to Maillardville twice a week from new Westminister. Started by the Shelly brothers, who moved to Vancouver from Ontario in 1910, their bread was popular and was delivered across the Lower Mainland.