Fighting to Be There: We Remember

“What good are these?”

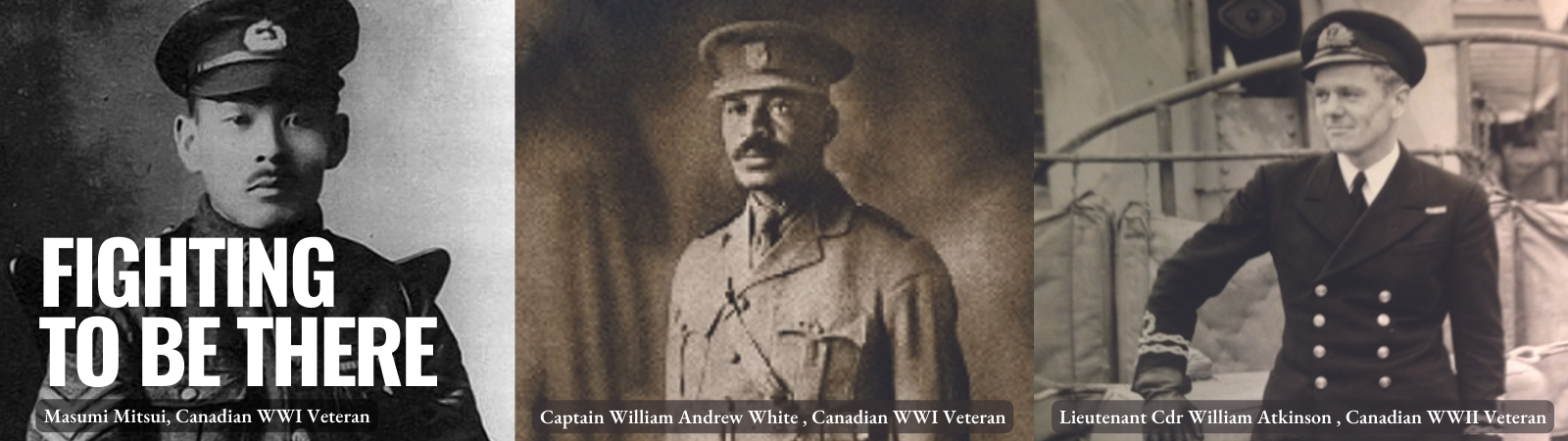

Many Japanese Canadians enlisted and demonstrated incredible courage in the First World War. Masumi Mitsui was one of them. He received the Military Medal for his excellent service after the War. However, the racism and discriminatory measures against Japanese Canadians only became worse when the Second World War began. In 1941, the Canadian government considered all ethnic Japanese as a “security threat” and sent them to internment camps. Angered, Mitsui threw his medals in front of BC Security Commission Officers and asked, “what good are these?” The bitterness of that moment remained with Masumi all his life.

On Remembrance Day, which is November 11 of every year, Canadians commemorate those who died fighting for our freedoms. And we honour those who survived.

This tradition originated from Armistice Day, which marks the end of World War One in 1918. Remembrance Day honours not only those who served in the past, but also to the current members of Canadian Armed Forces. Canadian Forces have made tremendous contributions to the World Wars and postwar peacekeeping operations. And their service has laid a cornerstone of our society today.

Fighting to Be There, at Mackin House from November 5 to November 19, is an exhibition that pays tribute to members of the Canadian military who served our country. This exhibition features direct quotes from veterans and shines a light on the experiences of a diversity of veterans.

Canada had been crucial to the downfall of the Nazi regime, for which the well-discipline and courageous Canadian soldiers in Italy, France, the Netherlands gained the reputation as both excellent fighters and a respectable force. However, many Canadian soldiers died and were wounded. Remembrance Day is an opportunity for Canadians to honour our veterans and deceased armed forces.

However, under the surface of patriotic pride, many issues have not been properly addressed. From the First World War onward, veterans have remained vulnerable to PTSD and other mental health issues. Many have difficulties to return to normal lives. Furthermore, many soldiers and veterans had been mistreated because they were different.

Fighting to Be There aims at truly honouring our veterans by revealing their experience. This exhibit not only focuses on brave Canadian troops and war narratives, but also illuminates the challenges and unfair treatment that members of the armed forces faced during their military career and afterward. The story of Masumi Mitsui illustrates that the history we are proud of today, was not always glorious, at least not for everyone. Indeed, Mitsui was not the only victim of racism.

Racism was so predominant in the Canadian military, where racial segregation was in effect for decades. On February 1, 1917, at the age of 42, Captain William Andrew White enlisted in the No. 2 Construction Battalion, an all-Black segregated unit of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The only Black officer in the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I. Captain White was also the only Black chaplain who served in the Canadian or British forces during the war.

By 1915, at least 200 Black Canadian volunteers had tried to enlist for the war, only to be rejected as many white soldiers refused to serve with Black men. Military headquarters in Canada faced pressures from all sides as Black leaders questioned why their community was not allowed to serve and why Military officials tried to prevent Black men from enlisting.

The idea of an all-Black infantry was not an option since they didn’t have enough Black men to run such a battalion and even if they did, the British War Office refused to allow Black units into combat as they feared that a Black infantry would use combat training against British authorities in the colonies.

In April of 1916, the Military headquarters proposed a Black labour battalion as an alternative solution, labour was in short supply at the time and were a critical aspect of support campaigns. The proposal was approved and recruitment began later that summer throughout the country. While enlistment was good, they did not have enough members to form an official battalion and were reformed as a labour company and renamed the No. 2 Canadian Construction Company. The Canadian Forestry Corps needed labour to help with their forestry operations in France and the Construction Company arrived in May of 1917 to begin work.

They primarily performed supporting tasks such as fixing logging roads and helping to build a logging railway. They also maintained the water and electrical systems for the camps, and transported finished lumber to the railway stations. The lumber they assisted with collecting was used for supporting the trenches, building gun platforms, ammunition boxes, and accommodation huts. With the support of the No. 2 Construction Company, mills were able to produce over twice the regular amount of lumber. While racism prevented African Canadians to join battles, this group still made tremendous contribution to the war effort.

Just like racial minorities, LGBTQ2+ soldiers also suffered discrimination. During the 1950s and 60s the Canadian military began a vetting process hidden behind guises of medical exams and hunting cold war spies in order to actively out and dismiss gay men from the service. Lieutenant Commander William Atkinson of the Royal Canadian Navy was forced to resign in 1959 after a year long investigation into his sexuality. He was forced to not only give up his distinguished career but his pension as well, leaving him financially unsupported.

After being forced out of the military, Atkinson wanted to share his story publicly and reach out to others in similar positions, and anonymously published accounts of his experience. His account served as well documented proof of the military’s history of dismissing gay men and allows us to remember this period of discrimination.

Despite of their service, many soldiers and veterans were subjected to discrimination and mistreatment because of their racial identity and sexual orientation. Many were denied the rights of pension

Some may ask why are we are exposing “unpleasant” history on a day of honouring our past? Coquitlam Heritage believes the more open we are to the past, the better our society will be in the future.

If we pretend negative sides never exist in our past, and only present a sanitized version of our history, the same mistakes will be repeated. Moreover, covering up parts of our past only undermines the integrity of our history. To truly honour our veterans, we must reveal the reality they once experienced.

Unfortunately, the number of Canadian veterans from World War II and other conflicts is decreasing every year. It is crucial to remind ourselves that when we enjoy living in a country of freedom, rights, diversity, and democracy, we must not forget those who fought for these values.

Lest We Forget.

Our exhibit Fighting to Be There includes the stories of Force 136, George Chow, Misumi Mitsui, William Andrew White, William Atkinson, Dick Patrick, Elsie Macgill, Michelle Douglas, and others. It runs from November 5 to November 19, 2022 at Mackin House.

We are open Remembrance Day, November 11 & Saturdays, 10 am - 4pm. Open Tuesdays to Fridays, 11 - 5pm.