Fighting to Be There

Fighting to Be There speaks of the many soldiers with diverse backgrounds, who hoped their military service would bring recognition and integration into society, but in the end, failed to receive this vital support from their country. This online-exhibit addresses the often-flawed treatment veterans received. In their own words, soldiers like First Nation Soldier Dick Patrick, Afro -Canadian soldier Andrew White and Michelle Douglas tell this story.

Francis “Peggy” Pegahmagabow

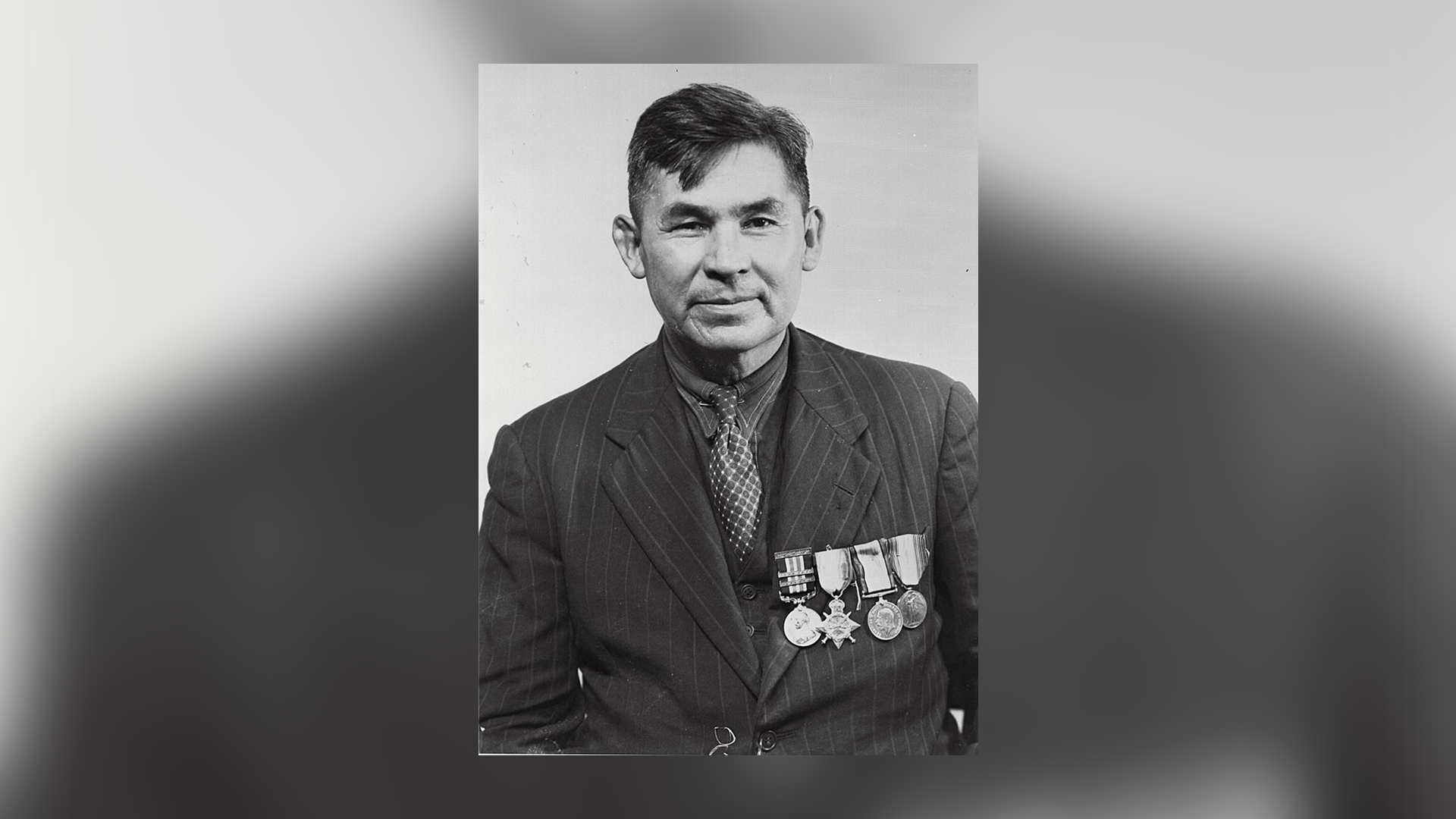

Photo of Pegahmagabow. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

Francis Pegahmagabow was an Indigenous soldier fighting in the Canadian Army during the First World War. He was born on March 9th, 1891, on the Perry Island Reserve in Ontario and was raised in many of the traditional ancestral ways of his people, learning to hunt, fish, and practice traditional medicine. Pegahmagabow sought to attend public school after working in lumber camps throughout his teen years, where he was remembered as a good student who often excelled in his studies. Upon graduation, he became a marine fireman before the Great War broke out. He was determined to serve when the war broke out in 1914, despite the government discouraging non-white people from enlisting in the army. Pegahmagabow persevered, and after being declared physically fit, he left for service in France. He was a part of the 1st Canadian Infantry Battalion and bore witness to many of the horrors of the First World War. He was present at the infamous Second Battle of Ypres, where the Germans first employed the use of poisonous Chlorine Gas. Although half of his battalion was wiped out, Pegahmagabow survived the ordeal.

-

Pegahmagabow gained a reputation as a outstanding sniper during the war and he is officially credited with 378 kills, the most out of any sniper during the war. He was regarded by his fellow soldiers as fearless, sneaking out onto no mans land at night in order to attack German patrols. This type of operation was extremely dangerous, and Pegahmagabow was away from the relative safety of the Canadian trenches. He was also strongly connected to his Indigenous identity – during the war, it was not uncommon for him to wear moccasins during missions where stealth was paramount. Compared to the hobnailed boots that were issued as standard, these shoes made far less noise when walking, allowing Pegahmagabow to remain hidden during his nighttime missions into no man’s land.

Pegahmagabow became a highly decorated soldier, the most decorated Indigenous soldier in the army at the time. He was

awarded the Military Medal, earning two separate bars for it. Only 39 soldiers received a second bar. He also received the 1914-15 Star, The British War Medal, and The Victory Medal. It is speculated that Pegahmagabow did not receive a higher honour, such as the famed Victoria Cross, due to his Indigenous background.

Following the war, Francis Pegahmagabow was involved in the fight for Indigenous rights. Despite being a heavily decorated war hero, he still faced racism and discrimination from fellow Canadians and the government. He led the Perry Island Indian Band, now called the Wasauking First Nation from 1921-1925, seeking more control for Indigenous people to overrule the government and decide what was best for themselves. He was eventually ousted after a power struggle, failing to get re-elected. Some regarded him as difficult to get along and work with. This has been attributed most likely to the trauma he suffered during the war, as PTSD was not a recognized or well understood issue at the time.

“When I was at Rossport, on Lake Superior, in 1914, some of us landed from our vessel to gather blueberries near an Ojibwa camp. An old Indian recognized me, and gave me a tiny medicine-bag to protect me, saying I would shortly go into great danger. The bag was of skin tightly bound with a leather throng. Sometimes it seemed to be hard as a rock, at other times it appeared to contain nothing. What was really inside I do not know. I wore it in the trenches.”

Photo of Pegahmagabow in 1945 at the formation of the National Indian Government in Ottawa. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

Photo of White. (courtesy of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic)

William Andrew White

On February 1, 1917, at the age of 42, Captain William Andrew White enlisted in the No. 2 Construction Battalion, an all-Black segregated unit of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The only Black officer in the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I, Captain White was also the only Black chaplain who served in the Canadian or British forces during the war.

-

By 1915, at least 200 Black Canadian volunteers had tried to enlist for the war, only to be rejected as many white soldiers refused to serve with Black men. Military headquarters in Canada faced pressures from all sides as Black leaders questioned why their community was not allowed to serve and why Military officials tried to prevent Black men from enlisting. The idea of an all-Black infantry was not an option since they didn’t have enough Black men to run such a battalion and, even if they did, the British War Office refused to allow Black units into combat as they feared that a Black infantry would use combat training against British authorities in the colonies.

In April of 1916, the Military headquarters proposed a Black labour battalion as an alternative solution, labour was in short supply at the time and were a critical aspect of support campaigns. The proposal was approved and recruitment began later that summer throughout the country. While enlistment was good, they did not have enough members to form an official battalion and were reformed as a labour company and renamed the No. 2 Canadian Construction Company. The Canadian Forestry Corps needed labour to help with their forestry operations in France and the Construction Company arrived in May of 1917 to begin work.

They primarily performed supporting tasks such as fixing logging roads and helping to build a logging railway. They also maintained the water and electrical systems for the camps, and transported finished lumber to the railway stations. The lumber they assisted with collecting was used for supporting the trenches, building gun platforms, ammunition boxes, and accommodation huts. With the support of the No. 2 Construction Company, mills were able to produce over twice the regular amount of lumber

“Imported—as if conquerors—to France. we black men decamped to this war with drums barking, bagpipes bawling, first disciplined by threats of lynching and frets of Klan, only to discover our old-new discipline is Labour— unreneged Negro Slavery…”

Masumi Mitsui

Photo of Matsui at the end of the First World War, after receiving a promotion to the rank of sergeant.(courtesy of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic)

Masumi Mitsui was born in Tokyo on 7 October 1886. Born into a Military family, Masumi wanted to join the Japanese navy but failed the entrance exam. Feeling he let down his native land, Masumi emigrated to Canada in 1908. He found work initially as a labourer on a farm in Richmond BC before moving to Victoria where he worked as a waiter at the Union Club. With the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, thousands of young men across Canada rushed to join Canada’s newly forming Expeditionary Force. For Japanese Canadians living in British Columbia like Masumi, their services were not wanted; enlistment offices in BC turned Japanese Canadians away. Like other racialized minorities of the era, Japanese Canadians were denied basic civil liberties, like the right to vote, enjoyed by other Canadians and experienced discrimination.

-

Yashshi Yamazaki, the publisher of the Japanese community newspaper in Vancouver, pushed for the acceptance of Japanese Canadians into the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF).1 By early 1916, he arranged for the training of 171 volunteers, including Masumi, for military service. Despite the need for men overseas, racially biased local recruiters were still not interested. However, when it was learned that recruiters in Alberta were accepting Japanese Canadians, more than 160 left BC, including twenty-nine-year-old Masumi, for Calgary. During the war Masumi demonstrated incredible courage. Masumi was awarded the Military Medal for his actions.

Despite their war service, Japanese Canadians did not receive voting rights upon returning home. It took years of struggle until 1931 when the provincial government finally passed a bill allowing Japanese Canadian veterans the right to vote, a bill that passed by a single vote on its third attempt through the legislature. The victory was bittersweet; although the veterans could now vote, the same right was not extended to their families.

Mitsui was president of the legion, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, in this fucntion he sned a message of loyalty to the Prime Minister and the Minister of Defence. But his declaration of loyalty counted for little. Mitsui soon learned that his successful Port Coquitlam poultry farm would be seized and that he and his family would be forcibly relocated one hundred miles inland. Before he was taken to the internment camp, an angry Masumi threw his medals on the floor of the BC Security Commission office asking, “what good are these?” The bitterness of that moment remained with Masumi all his life.8 Years later in 1985, Masumi represented his comrades at the relighting ceremony at Japanese Canadian War Memorial lantern in Vancouver’s Stanley Park. The flame had been extinguished during the wave of anti-Japanese sentiment in 1942.

“What good are these?”

Photo of Japanese Canadian Soldiers of the 10th Battalion in France. On the second row, far left is Masumi Matsui. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

Photo of May. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

Wilfred “Wop” May

Wilfrid “Wop” May was another influential Canadian pilot. Starting the war on the ground, May rose through the ranks before joining the RNAS (Royal Naval Air Service) late into the war. May was a successful fighter pilot during the war, proving himself with the downing of 15 aircraft.

-

May was flying as a subordinate to Brown during a fateful mission on April 21st, 1918. May and Brown encountered Manfred Von Richthofen, more famously known as the Red Baron, who was also flying with a subordinate, his cousin Wolfram. Brown ordered May to stay out of the fight between himself and the Red Baron. While observing, May noticed Wolfram doing the same, and attacked him. This prompted the Red Baron to pursue May, chasing him over Australian trenches. Brown fired on Richthofen and was officially credited with the kill. However, analysis suggests that gunfire from the Australian Cedric Popkin is what killed the Red Baron.

After the war, May stayed in the sky. He and a friend ran one of Canada’s first aerodromes, named May Field, on a rented pasture. May was hired in 1921 to ferry two ski equipped Junkers planes up North. This marked one of the first flights of its kind, beginning the Canadian aviation tradition of bush flying.

In 1928, May and another member of his flying club found themselves racing to Little Red River, Alberta, in a small plane with inoculations to prevent the spread of a diphtheria outbreak. May battled low quality fuel and a lack of infrastructure in order to complete his “Race Against Death,” garnering much media attention for the heroic act. Using this fame, May was able to establish Commercial Airways, an airline that helped to service the many remote parts of northern Canada.

Wop May also became involved with the Hunt for the Mad Trapper. In 1932, Albert Johnson shot deputies of the RCMP when they were serving a warrant at his Cabin in Rat River. Once a manhunt ensued, the RCMP hired Wop May to search for the Mad Trapper by air, looking for his footprints in the snow. May’s involvement was critical to the finding and confronting of Johnson. After the gunfight ended, May was able to land and rescue a critically injured officer. Had May not done so, it is likely that the man would not have received medical treatment for his gunshot wounds in time. May would eventually die due to a stroke while hiking with his son in June of 1952.

British soldiers loading a battery of Livens gas projectors. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

Malignant Futility

The etchings made over 100 years ago by an unknown German artists (we only know the initials W. A.) are bleak and haunting, depicting the mindset and experiences of WWI soldiers going into battle, facing a new and unknown war. The sharp lines, explosions, and skeletons show the war’s violence and destruction while the downtrodden faces and dark skies imply the malaise of soldiers heading to a near-certain death; as Robert Musil, an Austrian soldier and poet, wrote, going into battle was accompanied by a feeling of “malignant futility”. As capsules of meaning, these etchings reflect a wider trend in WWI-era art and the effects of the war.

-

WWI brought the world’s first mechanized war, as the advances of the Industrial Revolution made warfare mechanized and death more commonplace. Socially, WWI was a shock to the system for Europe. Aside from relatively minor conflicts in Southern Europe and short wars of succession in Northern Europe, the continent had enjoyed peace since the late 18th century. In the interim, the Industrial Revolution swept across the continent, bringing unprecedented changes to Europe. More than a peacetime affair, the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution fundamentally changed warfare. New inventions such as machine guns, mustard gas, tanks, and armoured vehicles tore through armies, killing thousands and leaving a spectacle of death in their wake. Soldiers and civilians alike were left in shock, having never before seen such a scale of destruction, death, and loss. In describing WWI, the term “industrialized slaughter” became popular.

In capturing this fractious era, artists were essential in communicating the horrors and trauma of war. Photographers on the front lines brought the war into the home with images of amputees, cramped conditions in camps, and dead bodies strewn across trench-scarred battlefields. Meanwhile, painters and other artists communicated the emotional and human response. A new modern art movement called Vorticism emerged, with painters Wyndham Lewis, David Bomberg, and Paul Nash leading the movement’s visual art trends. Lewis and Bomberg were particularly infl uential, with Lewis being hired by the British and Canadian militaries as an official war artist and Bomberg using his experiences during the war to inform his painting. Lewis’ most famous work is A Canadian Gun-Pit, while Bomberg’s most famous painting is Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunneling Company. Both paintings show life in the trenches, using a jagged, abstract style to portray dozens of men readying artillery and building trenches. Similar to the style of the etchings, the obtuse modernist art is a reflection of both artists’ lack of faith in the trajectory of the modern, mechanized age and a disillusionment with newly industrialized warfare, a common sentiment amongst WWI veterans and civilians alike.

Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company, Hill 60, St Eloi by David Bomberg, which bears a reference to 1st Canadian Tunnelling Company. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

Spring in the Trenches, Ridge Wood, 1917 by Paul Nash. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

Photo of MacGill. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

Elsie Macgill

Elizabeth ‘Elsie’ MacGill, born 1905 in Vancouver, became the first woman to earn a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, the first practicing Canadian woman engineer, and, in 1938, became the chief aeronautical engineer of Canadian Car & Foundry, where she headed production of Hawker Hurricane fighter planes during World War II.

-

MacGill began her education studying applied science at the University of British Columbia before moving on to study electrical engineering at the University of Toronto, becoming the first woman to be admitted into their engineering program. Originally, she primarily worked with automobiles but became interested in airplanes after the company she was with switched to aircraft manufacturing. By 1929, MacGill completed her master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, becoming the first woman aeronautical engineer in the world.

She returned home to Vancouver after getting polio and spent her time in recovery drafting aircraft designs. She was eventually offered a job as an assistant aeronautical engineer for Fairchild Aircraft Ltd, where she created numerous aircraft deigns and conducted test flights to monitor the performance of those designs. MacGill became the chief aeronautical engineer for Canadian Car & Foundry in 1938 and was also accepted into the Engineering Institute of Canada, becoming their first woman member. During her time with Canadian Car, she retooled their factory and re-trained the workers to mass produce Hawker Hurricane aircrafts, one of the main fighter planes used by Canadian and Allied forces in WWII. She oversaw the production of 1,1451 Hawker Hurricane planes and designed a new version with skis and de-icing equipment. She was dubbed by American media as “Queen of the Hurricanes.”

After the war ended, she continued as an aeronautical consultant and worked towards raising awareness for women’s rights. She became a leader for the Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Club, as well as serving on the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada.

“War effort is a man staying and working an extra hour, or two, or five hours a day. It is a woman cutting short her noon hour to get back to finish the job; it is someone taking home his problems to solve them after dinner; it is someone coming back in the evening to finish an assignment. War effort is something, which is as microscopic in the unit as the individual, but as mighty in the sum total as an army.”

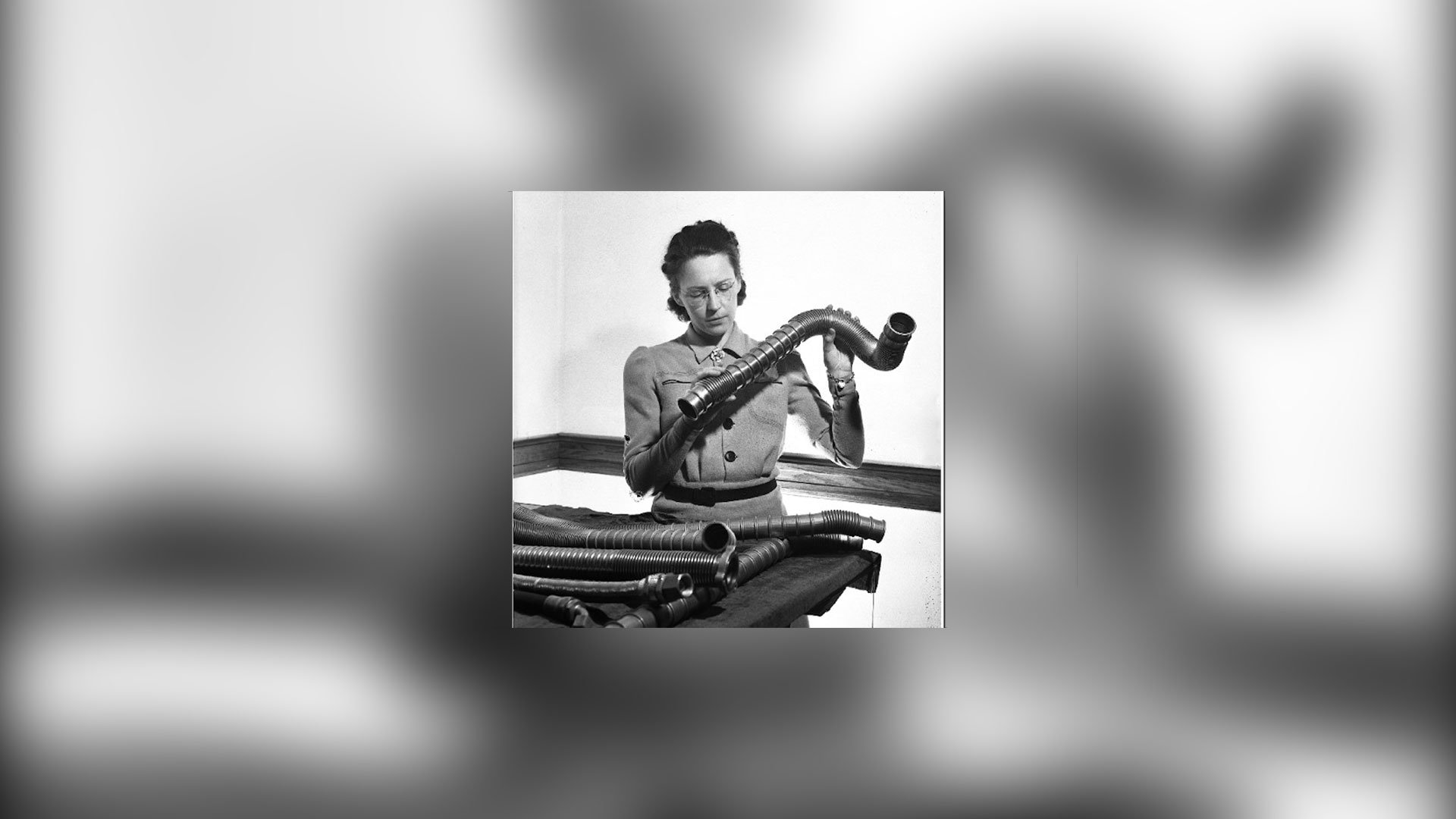

MacGill checking the welding on pipes during her time as Chief of Aeronautical Engineering at Canadian Car & Foundry, 1938-1943. (courtesy of Canada Aviation and Space Museum)

A comic book series in 1942 that published a story on MacGill called True Comics. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

George Chow

Photo of Chow. (courtesy of Veterans Canada)

George Chow, born in Victoria in 1921, served in the Canadian gunner crew that shot down the first German plane on English soil. He would go on to become a Master Warrant Officer in the position of a Battery Sergeant Major before being honourably discharged in 1963.

-

After the start of World War II, Chow secretly signed up at a recruiting centre in Victoria without his parents’ knowledge, just two months shy of his 19th birthday. He was sent to the Seaforth Armoury in Vancouver a week later to complete basic training, before joining the 16th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery in Ontario. He was later assigned to a base in Colchester, England, where his team shot down the first German plane on English soil. George Chow later became a member of the 2nd Army Group Royal Artillery during the Normandy Campaign, and fought inland in other regions of France before heading into Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands.

After the war ended, Chow joined the 43rd Heavy Anti-Aircraft of the Royal Canadian Artillery in Vancouver as a Gunnery instructor. He was awarded numerous medals for his war efforts, including the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal, the rank of Knight of the National Order of the Legion of Honour, and the Medal of Legion of Honour.

Photo of a young George Chow in England, 1943. (courtesy of Juno Beach Centre)

Photo of Patrick. (courtesy of Omineca Express)

Dominic “Dick” Patrick

Dominic ‘Dick’ Patrick was born in 1920 in the Saik’uz First Nation near the centre of British Columbia. He was a Residential School survivor, decorated World War II vet who ventured behind enemy lines and single-handedly captured over 50 enemy soldiers, and an outspoken advocate for Indigenous rights and practiced civil disobedience in his fight for inclusion.

-

When he was 22, Patrick volunteered to serve in World War II, one of at least 3,000 First Nations members who joined as part of the Canadian Armed Forces. As one of 15 Saik’uz soldiers who had volunteered for service, he served with the 5th Canadian Anti-Tank Regiment in the 4th Canadian Armoured Division as a gunner, and was a crew member on an M10 self-propelled anti-tank gun. However the nature of military life during the war meant that he was accepted in a way not shown to him back in Canada.

In 1945, King George VI awarded Dick Patrick the Military Medal for gallant and distinguished conduct for his efforts in Belgium after the Normandy landings. In the days after D-Day, Patrick helped Canadian forces dislodge German defenses and, under heavy artillery fire, helped to secure and hold an important river crossing. While Allied troops eventually made it across the river, bad weather conditions and enemy fire made it difficult to determine German positions. Patrick went ahead on his own by foot and succeeded in pulling off a surprise attack on an enemy machine gun position. His attack forced 52 soldiers and officers into surrender and cleared out a strong point, allowing the infantry to enter.

Force 136

During World War II, many Chinese Canadians were turned away when they tried to enlist. Approximately 600 Chinese Canadians were either rejected from service or were never called to active duty. Despite their classification as second-class citizens, immigration bans, and being unable to vote, many Chinese Canadians saw military service as a means of fighting for citizenship. Eventually, the bombing of Pearl Harbor opened recruitment, as the British Special Operations Executive sought to form a special task force.

-

Force 136 was a special unit that was established after Japan occupied parts of Southeast Asia. British Forces recruited 150 Chinese Canadians to infiltrate enemy lines and help resistance fighters sabotage Japanese lines and equipment. Chinese Canadians were the perfect recruits, as they could easily blend in amongst Southeast Asians and had the ability to speak English, Cantonese, and Mandarin, making them flexible when infiltrating occupied spaces.

New recruits began training near Lake Okanagan in silent killing, wireless operations, demolition, stalking, and rolling out of vehicles. They were then sent to bases throughout Southeast Asia where they trained in tailing, parachuting, surveillance, Japanese military weapons, and jungle survival. Each member of the unit was given a special kit which included an opium pill for trading, and a cyanide pill in case of capture.

While many members of Force 136 had not been deployed on a mission by the time Japan officially surrendered, the Force still conducted many missions around Southeast Asia as members operated out of Burma, Borneo, Malay, and Singapore. Select units had parachuted outside of Japanese-occupied Kuala Lumpur and worked to disable telephone lines, blow up railway bridges, and

join forces with the Anti-Japanese Army in Malay. Another unit lead by Roger Cheng, the first Chinese Canadian officer in the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, dropped into Borneo to make contact with the Indigenous peoples of the area before joining a British team to gather information on British prisoners of war. Many Chinese Canadian members stayed in Southeast Asia after the war ended to assist with liberating prisoner of war camps, pushed back on revenge massacres, and helped to maintain order in a post-surrender environment.

All 150 Chinese Canadian members of Force 136 survived the war, though many dealt with ongoing health issues from the jungle living conditions and diseases while deployed in the field.

Photo of Force 136 in England waiting for repatriation to Canada. (courtesy of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum)

“When I wanted to enter the army in Canada I was refused. At that time they did not take any Chinese-Canadians in the armed forces. We were second-class citizens. We were not allowed to go to university or take special training. We were only allowed to work in grocery stores, restaurants, things like that.”

Not Always Welcome

World War II

The effects of World War II resulted in a shift in gender roles within Canadian society. As men left to fight as soldiers, women took up the work left behind, resulting in a homosocial community at home and on the front lines. Close relationships developed between soldiers, and homosexual relationships were not uncommon throughout the battlefield. Although homosexuality was policed by the military, identifying and censoring such relationships became difficult due to wartime dynamics blurring the lines between gender norms. Soldiers had close friendships that were difficult to distinguish from romantic ones, and even cross-dressing became a regular occurence within military camps to boost morale through performance. There are only a few records of wartime homosexual experiences, due to the discrete practices of those involved and the censoring of any evidence by the military. As part of the process of vetting gay men, the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps developed a medical examination system that classified homosexuality as a “psychopathic personality.” Anyone receiving that assessment automatically became medically unfit to join the service and was regarded as untrustworthy.

-

The military also targeted gay men already in service by discharging anyone they perceived to behave in a “scandalous manner.” Those discharged were denied various rights and often faced penalties that threatened imprisonment. Some soldiers found safety in the fact that the military made a distinction, between those they saw as “true homosexuals” and those they saw as just someone dealing with the fact that there were no women present. Not all cases were treated equally, with the perceived threat of gay men mainly centred around higher commanding positions lower level soldiers were able to sometimes go under the radar. “Thousands of dedicated men and women in the federal civil service and the military had their careers destroyed and their lives dramatically altered in the 1950s and the 1960s in the same of ‘national security,’ solely because of their sexual orientation. In many cases, those affected suffered in silence, piercing together their lives as best as they could. Others resisted in a variety of ways. But everyone would bear the scars.” – Lesbian and Gay Archivists, no. 15, 1999.

Photo by Martijn Hendrik. (courtesy of Unsplash)

Cold War

By the late 1950s, concerns about national security brought on by the Cold War led to an intensified policy of identifying and dismissing LGBTQ2+ members from the military and civil service. The military employed many tactics such as spying on off-duty soldiers, trying to trick soldiers into outing themselves through mental interrogation and pressuring soldiers to out each other. Many soldiers revealed to be gay were given a choice to either resign with an honourable discharge or be court-martialed. This process was further intensified throughout the 1970s, with the Canadian Forces enacting an official administrative order to ban “sexual deviates” in the force, and extending their law to target lesbians as well. Because homosexuality was classified as “scandalous” or “disgraceful” conduct, it continued to be a punishable offence.

-

This policy continued into the early 1980s when the military argued that LGBTQ2+ individuals would cause a conflict in morale and have a “detrimental effect on operational efficiency.” The policy began to be relaxed in the mid-1980s, when people had to consent to be discharged, but did not end until 1992. After the ban was reversed, the military reinstated positions and removed career restrictions on those previously discharged. In 2016, the House of Commons Defence Committee voted to amend the service records of LGBTQ2+ ex-military members. Finally, in 2017, the Canadian government offered a formal apology, a $145 million settlement for those affected by this policy, and promised renewed efforts towards reconciliation and memorialization.

Photo of Atkinson. (courtesy of Ron Levy, Huffington Post)

William Atkinson

During the 1950s and 60s, under the guise of medical exams and hunting Cold War spies, the Canadian military began a vetting process to actively out and dismiss gay men from the service. Lieutenant Commander William Atkinson of the Royal Canadian Navy was forced to resign in 1959 after a year-long investigation into his sexuality. He was forced to give up not only his distinguished career, but his pension as well, leaving him financially unsupported.

-

After being forced out of the military, Atkinson wanted to share his story publicly and reached out to others in similar positions, anonymously publishing accounts of his experience. His accounts served as well-documented proof of the military’s history of dismissing gay men, allowing us to remember this period of discrimination.

“We lived constantly in the shadow of disaster of some kind and were conditioned to try, at least, to roll with the punches. Like so many of us, I maintained a façade for most of my life, for viewing by non-gay society. It’s extremely difficult for me to open up to anybody because I spent so many years suppressing what I wanted to do or be and acting in the presence of the world.”

Photo of Atkinson. (courtesy of Wikicommons)

Michelle Douglas

Photo of Douglas. (courtesy of CBC Canada)

Michelle Douglas was born in Ottawa in 1963, joining the Canadian Armed Forces in 1986 where she served as an Air Force Lieutenant. She was eventually invited to join the Special Investigation Unit (SIU), becoming the first woman SIU officer. Despite the fact that the SIU was investigating gay and lesbian service members, and that she was a lesbian herself, Douglas took the position in an attempt to hide her sexuality.

-

The military focus on sexual orientation began during the 1950s, when it was believed that LGBTQ2+ individuals posed a security threat and were more susceptible to blackmail during the Cold War. Thousands of LGBTQ2+ individuals in the service were negatively impacted; they could no longer receive training, promotions, raises, and would get demoted or discharged. Soon after Douglas took her position with the SIU she was put under interrogation over her sexual orientation. Although she initially denied being a lesbian, she was eventually found out through a polygraph test and was dismissed in 1989.

Douglas filed a lawsuit against the military the following year and was eventually awarded $100,000. The Federal Court of Canada eventually ruled that LGBTQ2+ individuals could not be excluded from military service; it became a landmark ruling that formally ended the systematic military discrimination against LGBTQ2+ service members in Canada. Michelle Douglas has since worked for the Department of Justice and volunteered for numerous LGBTQ2+ rights organizations, receiving the Diamond Jubilee Medal in 2012 for her contributions.

In 2018, Douglas was featured in Sarah Fodey’s documentary The Fruit Machine, which recounts the personal stories of survivors of Canada’s decades-long homosexual witch-hunt.

Photo of Douglas. (courtesy of Historica Canada)

The Challenges of Returning

Many veterans struggle to find work after they return home. Because people often join the military right out of high school, they may not get the education required for many jobs. In Canada, the number of homeless veterans is estimated to be anything between 3,000 and 5,000 individuals, based on a 2019 statistic. Depression and suicide rates are also higher among people who have served in the military. The reason why people do not get the help they need is due to the social stigma attached to issues of mental health.

As of 2021, more than 40,000 Canadian military personnel have served in Afghanistan, with roughly the same number having served as peacekeepers in Bosnia. According to a 2011 study, 14 percent of returning military personnel have been diagnosed with a mental illness. Additionally, the Anxiety and Depression Association of America writes that 67 percent of people exposed to mass violence will develop post-traumatic stress disorder.

-

It can be very difficult to adjust to a “civilian” mindset, especially for soldiers returning from a war zone. Repeated deployment frequently increases the difficulties of readjusting to civilian life. Two groups that tackle such issues are the Veteran’s Transition Network (VTN), co-founded by UBC counselling psychologist Marvin Westwood, and the Vancouver Island Compassion Dogs (who provide therapy dogs).

In previous wars, returning home proved extremely problematic for non-white soldiers. Upon returning home, many had hoped for animprovement in socioeconomic status and civil rights. Yet they encountered the same social ills and racist violence which they faced before the war. They hoped to have “proven their worth” to the nation and expected to earn their well-deserved dues, but failed to receive the respect that their white counterparts received.

Minority soldiers faced a long history of racism in the Canadian Forces. Before conscription was introduced in 1941, many people of colour volunteers were turned down as most military positions were reserved for soldiers of “pure European descent.” There is a sense of irony in the fact that, during a time when countries like Canada were fi ghting fascism overseas, they practiced intolerance and racial violence on their own shores. A recent report by the Minister of National Defence’s Advisory Panel on Systemic Racism and Discrimination states that, even in 2022, “Racism in Canada is not a glitch in the system; it is the system…” The report went deeper and listed many issues that prevented Black, Indigenous, LGBTQ2+, and women members within the ranks, as well as the barriers facing Canadians with disabilities.

This leads to the issue of the Armed Forces seeing a decline in recruitment as many groups turn away from the forces as a viable option for integration. Sadly, military culture has favoured white male cisgender members, while exposing other groups to abuse and discrimination.

Photo by Martijn Hendrik. (courtesy of Unsplash)