38th Parallel: The Korean War

Intro To War

On June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded the Republic of South Korea, beginning the Korean War, often referred to as “The Forgotten War.” South Koreans refer to it as 6.2.5 (June 25th, when the conflict officially began), and North Koreans call it “The Fatherland Liberation War.”

To understand this major conflict, it is necessary to look at the situation in the world just after World War II. Japan’s surrender meant they were ousted from Korea, a country they had occupied since 1910. In their wake, the Soviet Union and the United States jointly occupied the peninsula, dividing their zones of control along the 38th parallel. Unable to come to an agreement over the reunification of Korea, they aided in the foundation of North and South Korea respectively.

The world, at this time, was weary of war, poorly prepared for another, and hoped to avoid a long, drawn-out conflict. Partly for this reason, Canada and the other United Nations did not officially declare war, but intervened as part of the UN initiative to restore peace.

The Korean War claimed between 2-3 million civilian lives during its course. To a large degree, these deaths were the result of exposure, starvation, and other logistical failures rather than direct military action. In all, South Korea suffered 990,968 civilian casualties while 1,500,00 North Korean civilians were injured or killed during the war.

26,791 Canadian military personnel were deployed to Korea. Another 7,000 served after the armistice was signed.

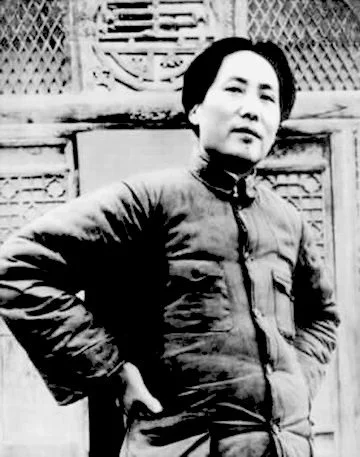

Major Figures

Minor Figures

Forces Contributes

Koreans and the Forgotten War

Civilians in Korea were severely affected by the war. As least half of the overall war casualties were civilians. The destruction of infrastructural targets, bombing of fields, and deforestation interrupted farming lead to many Koreans becoming refugees. They roamed the country to find food, shelter, and to avoid violence. South Korea lost between 300,000 and 600,000 civilians, and North Korea lost approximately 1 million.

Those who survived suffered from hunger, disease, and from the elements. Summers in Korea are hot, and winters can get bitterly cold. In addition to these difficulties, the terrain in Korea is rugged, with many mountains and hills, as well as hot and humid valleys in the summer. These conditions caused additional death, as under-nourished people tried to find safety.

The war also created a very large orphan population. Some estimates say as many as two million children were left alone during the war, and many more after the war ended. Many, if obviously of mixed race, were stigmatized and outcast. Approximately 180,000 were adopted by families in North America, Europe, and Australia. The remainder, if they survived, aged out of the adoption system and continued to live in Korea.

Young boys would often attach themselves to a military unit for survival. These “houseboys” cooked and cleaned for soldiers and moved with the troops. Sometimes these boys would be taught English, and after the war ended, many were sponsored by soldiers to come to Canada or other countries to continue their education.

When the conflict ended, the 38th parallel became the approximate division between North and South. Families separated by this line were, in many cases, separated for life.

Two refugee children stand in front of an American tank

Korean orphans at Jejudo, Korea.

Woman fleeing Pohang, South Korea in 1950.

South Korean refugees cross a frozen river to escape the fighting.

Refugees crossing a railway

A Korean orphan boy adopted by a motor pool battalion at Incheon.

Aerial and Artillery Bombardment

However, much of the suffering was cause or exacerbated by the UN bombing of infrastructural targets such as rail lines, the hydro-electric power grid, and countless other targets of either side of the 38th parallel. The result was a war that cost far more civilians their lives than combatants.

B-29 Superfortress drop their payload over Korea.

Over the course of the war, the United States Air Force and Navy would drop 635,000 tons of bombs on the Korean peninsula. The resulting devastation created inhumane conditions for the Korean people, and left a legacy of deforestation and contaminated soil.

An American F9F Panther Naval Fighter uses rockets to attack ground targets in North Korea.

Korean refugees abroad S.S. Meredith Victory in December 1950.

Combat in the Korean War

Soldiers on both sides of the Korean War faced battlefield realities unique to that conflict. UN bombers faced the new threat of attack from Soviet made Mig-15 jet fighters designed to counter them.

Meanwhile, North Korean and Chinese ground forces had to contend with a concentration of American rocket and bomb attacks that was unprecedented in the history of warfare. Both sides struggled with the climate and terrain.

In addition, UN troops were supported from the sea through Navy and Marine Corps aviation units that disrupted North Korean and Communist efforts, threatened their vulnerable coastline, and in some cases, turning the tides of battles.

Though UN Forces had the advantage of more artillery and tanks, they were vastly outnumbered by soldiers after China entered the war. Ultimately, the war would end in a frustrating stalemate along the 38th parallel, quite close to where the border had been three years prior.

This aerial view of Heartbreak Ridge, looking South, shows the rugged terrain just North of the 38th parallel, North Korea. The Battle of Heartbreak Ridge was preceded by a three-week battle the next ridge over, in which 2700 UN Forces were killed and there was an estimated 15,000 enemy casualties.

The Battlegrounds

Canadians fighting in Korea faced both extremely cold winters and very hot summers. Winter conditions subjected soldiers to colds, flus, frostbite, and trench feet. In the summer, they contended with heat rashes, reactions to unfamiliar and poisonous plants, foot problems, and insect bites which often became infected.

The terrain of Korea is mountainous and rugged. While in Korea, troop training focused on hill climbing. Torrential rains were common in summers, and in 1952, seven straight days of rain collapsed 150 Canadian bunkers when the Imjin River flooded twelve meters above its normal level.

Korean roads outside of cities were often just dirt tracks used by oxen and wagons, and ill-suited to the movement of troops and heavy military equipment.

Train Busting

“Train Busting” was a tactic employed by UN Forces that meant running in close to shore, usually at night and risking damage from Chinese and North Korean artillery, in order to destroy trains or tunnels on Korea’s coastal railway. Of the 28 trains destroyed by United Nation warships in Korea, Canadian vessels claimed eight. HMCS Crusader, pictured here, destroyed four trains, more than any other train buster.

Equipment

After WWII, many nations were ill-prepared for another war. The Canadian military had kept supplies for limited branches of the forces and sold off the remainder to other friendly nations and to the general public. Many nations considered it unlikely that another major world conflict would arise in the decade after WWII, and selling off old equipment was also a way to support Canada’s armaments industry.

Production over stockpiling was the favoured strategy. With the onset of the Korean conflict, Canadian troops went to fight with equipment that was close to becoming obsolete. Many of the other nations involved were in the same situation. Some examples of equipment can be seen below.

Hockey on the Imjin River

The Imjin hockey games took place in March, 1952. Hockey equipment was shipped out to Canadian soldiers in an effort to boost morale. The games were played on the frozen Imjin River with the sound of Chinese artillery in the background. It was the first time hockey had been played in Korea.

Teams were created amongst the Canadian Van Doos (R22eR), the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery (RCHA), the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI), and the Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR). The final game, for the Imjin Cup, was played on March 25 between the PPCLIs and the R22eRs. The Princess Patricia’s won, 4-2.

An eager crowd of Canadian soldiers watched their comrades play hockey on the Imjin River.

In 2013, the first Imjin Classic was played in Ottawa, to commemorate the games played during the Korean War. It has since become an annual event.

A group of entertainers perform for U.S. Troops.

Two Canadian soldiers allow a group of Korean children to play on their jeep.

American soldiers celebrate New Years Day, 1952.

Canadian soldiers partake in an outdoor service.

Puck drop at the first Imjin Classic, Ottawa 2013. Courtesy of the Senate of Canada.

Coquitlam and Korea

British Columbia has the second largest population of Korean Canadians in the country with around 54,000 primarily located in the Greater Vancouver Area.

Of these, approximately 8,000 call Coquitlam home. Coquitlam even has a sister city, Paju, in Korea. A few of Coquitlam’s notable Korean-Canadian citizens are below.

The Honourable Yonah Martin

The Honourable Yonah Martin is the first Canadian Senator of Korean descent to serve in the Senate of Canada, and the first Korean Canadian parliamentarian in Canadian history. She is the co-founder of the C3 Korean Canadian Society, a BC based non-profit founded in 2003 that aims to bridge communities through volunteerism and educational, cultural, and cross-cultural community building initiatives. In 2013, her Senate Public Bill (S-213) was enacted to annually recognize July 27, (the day on which the Korean War Armistice Agreement was signed in Panmunjom, Korea, 1953), as Korean War Veterans Day. She has been serving as Grand Patron of the Korea Veterans’ Association Heritage Unit since July 2017. In addition to numerous other awards from both Canada and Korea, Senator Martin was awarded the Tri-Cities Spirit of Community Award for Cultural Harmony in 2004.

MP Nelly Shin

MP Nelly Shin is Canada’s first ever Member of Parliament of Korean heritage. For the first year of her term, MP Shin held the role of Deputy Shadow Minister for Canadian Heritage. Currently, she is on the Standing Committee on the Status of Women.

While she was Deputy Shadow Minister for Canadian Heritage, MP Shin promoted multiculturalism and ethnic media, as well as recognizing the contributions of WWII Chinese Canadian veterans as part of our Canadian heritage.

Currently, MP Shin is actively advocating to stop anti-Asian racism and recently spoke at the Stop Anti-Asian Hate rally that took place in Coquitlam on March 8, 2021.

Steve Kim

Steve Kim is a Coquitlam City Councillor. He was born in Vancouver and has spent most of his life in Coquitlam. His parents, John and Sue, were children during the Korean War and have related stories to their family of the privations they suffered during the war. In the late 1960s they immigrated to Canada in search of opportunity and adventure. In the 1970s, after having two sons, they opened Vancouver’s first ever Korean restaurant and Korean food market, helping to establish the thriving community we know today.

Steve is an entrepreneur and small business owner, as well as an avid volunteer. In addition to serving as a councillor for the City of Coquitlam, Steve is also chair of the Economic Development Advisory Committee, Vice Chair of the Universal Access-Ability Advisory Committee, Council Representative on the Coquitlam River Watershed Roundtable, and Council Representative for the Tri-Cities Food Security Team.

Previously, he was a director of the Maillardville Residents Association, director of the Canada Korea Business Association, and joined Senator Yonah Martin as the other co-founder of the C3 Korean Canadian Society.

He is the first person born outside of South Korea to receive the Prime Minister’s Citation from the Blue House (Cheongwadae) in the Republic of Korea. This distinction is awarded to Korean diaspora around the world in recognition of community leadership and volunteerism.

Today, Steve’s family all live and work in Coquitlam and the Tri-Cities. None of this would be possible without the sacrifice of our Korean War Veterans.

Chang Uy Hong

Chang Uy Hong has been a Coquitlam residence for ten years and has lived in other places in Canada. Born in Korea, he was only four years old when he and some of his family joined the many refugees seeking safety during the war, and witnesses the suffering of the Korean people caused by the war. He, his mother, and other relatives walked from place to place, carrying the younger ones who could not walk. They saw the dead, witnessed bombing and managed to survive. As an adult, Mr. Hong served in the Republic of Korea’s air force as a jet fighter mechanic, and later in life immigrated to Canada. In Canada, he became a member of the Honorary Korean War Veteran’s Association and met many of the veterans who fought for his country. He is the president of the Korean War Cenotaph Committee. He contributed many of the images shown in this exhibition.

Veterans of the Korean War

-

Bill Newton was a combat medic with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry during the Korean War, during which time he was posted to Hill 187, the Battle of the Hook. While under fire there he treated 24 men and was recommended for bravery. Due to lack of witnesses, he received the Oak Leaf metal, given for “Mentioned in Dispatches.” Mr. Newton would have been well acquainted with the Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals, or M.A.S.H., made famous by the 1970s television show of the same name. Bill was also involved in the battle on Hill 355. Hill 355 was so called because it was at 355 feet elevation, which made it a strategic high point, north of Seoul. Bill did two tours in Korea. His military career, which also included three years in Germany, spanned about a quarter of a century.

-

Peter Howard was a platoon sergeant who served with the British forces during the Korean War. He and his unit spent most of their time on a hillside called The Hook, where they lived in a hole in the ground. Deprived of sleep, they rebuilt barbed wire fences and disposed of the dead, and either patrolled the area or fended off the enemy. One night they were mistakenly bombed by the US forces. On another occasion, his platoon was crossing a wide river when they were caught be enemy fire. Their inexperienced, new platoon officer ignored the standard procedure of leaving the Bren gun on the safe side to provide covering fire, and as a result they were sitting ducks, Peter was subsequently wounded and flown out to Japan for treatment. He was still removing pieces of shrapnel from his body many years later. While there, his service time expired and he could have returned to Britain, but chose to enlist a second time, returning to Korea. Mr. Howard was also a veteran of WWII, serving as a volunteer aircraft spotter during the Berlin Air Lift. He lived on Cottonwood Avenue in Coquitlam and ran the Dogwood Rose Garden before he passed away in 2020.

-

Frank Smyth enlisted in the Canadian Army in 1950 at the age of 17 and trained to become a paratrooper. He tried twice to go to Korea with his infantry unit, but was stopped because of his age and punished. He tried to get his documents altered to say he was older, but with no success. He then joined the Canadian Provost Corps (the Military Police) and after training, arrived in Korean when the war had ended. At the time, it was uncertain whether or not the ceasefire would hold, so he was in Korea for two years. After also serving in Egypt, Lebanon, Cyprus, and Jamaica with Canada’s Peacekeeping operations, Mr. Smyth was granted a voluntary release from the service in1970. Frank and a WWII veteran, Russell Hellard, have been very active in the community, visiting schools to talk about war and veterans, as well as contributing to the Dogwood Veterans publication, edited by Russell Hellard.

Remembering the Forgotten War

Though often referred to as the Forgotten War, the efforts of people like Yonah Martin, Chang Uy Hong, and surviving veterans like Frank Smyth, Leo Valentine, Russell Hellard, and Bill Newton, have ensured that the sacrifices of those who fought are not forgotten.

There are numerous places in Korea that commemorate the soldiers who fought and those who died. Here are some from our local communities.

Gapyeong Monument, Langley

This monument is located at the Derek Doubleday Arboretum in Langley, BC. The stone came from the region where the battle of Gapyeong was fought, sent by South Korea as a gesture of appreciation for Canada’s involvement in the war.

This battle is considered a turning point in the Korean conflict, during which the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment held off an entire Chinese division on April 23, 1951. They prevented the capture of Seoul.

Ambassador of Peace, Burnaby

The Korean Veterans Association of Canada donated The Ambassador of Peace Monument to the City of Burnaby in 2007. Located in Central Park in Burnaby, the monument has three parts. There is a memorial, a statue created by South Korean artist Hyun Kuk Cho who now lives in British Columbia, and a wall of plaques recognizing the 36 servicemen from British Columbia who died in the Korean War. The Burnaby Korean-Canadian community raised nearly one million dollars for the creation of the monument.

North Burnaby Cenotaph

Located in Confederation Park, the North Burnaby Cenotaph has plaques commemorating those lost in WWI, WWII, and the Korean War. It was built in 1953 by WWI veteran Walter Holmes Morrice, and erected by the North Burnaby Legion Post #148.

Additional monuments to those who served are found in Veterans Park in Port Coquitlam and Blue Mountain Park in Coquitlam.

Korean Book of Remembrance

Canada keeps Book of Remembrances, and there is one for the Korean War located in the Peace Tower in Ottawa. This book contains the names of 516 Canadians who died in service during the Korean War. Of these, nearly 400 are buried in the United Nations Memorial Cemetery in Busan, South Korea.